The 2011 International Symposium on QFD was hosted in Stuttgart Germany. It was attended by many German automotive and manufacturing engineers, IT professionals, consultants, EU scholars, and Japanese Quality experts, among others. Even in this age of instant electronic communication, there is always something irreplaceable that we find in face-to-face interactions and personal exchanges that open our eyes and minds to fresh insights.

On this occasion, my new discovery involved the choice of language in German business world. I was surprised that often the Germans preferred the English word "customer" to the German word "kunde." It was explained to me that in German, the term kunde carried a negative connotation, which by using English, could be avoided.

So, I thought I would do a little etymological investigation of the English, German, and Japanese words that translate into customer, and see what deeper meanings might be discovered.

Customer, in English, emerged in the late 14th century as travel and trading became liberalized in the Renaissance. It originally referred to customs officials responsible for collecting a toll or tax on traded goods. The word came to English by way of French, from the Latin word consuetudinem meaning "habit, usage, way, practice, or tradition." The Latin itself comes from com (meaning "together") and suescere (meaning "to become used to, accustom oneself)." By the 16th century, the meaning has evolved into "a difficult person to deal with" and Shakespeare later even used it to mean "prostitute."

Here is my thoughts on the English word customer: This is a person who can pass or deny a transfer of goods; a person that has certain practices or ways of doing things that must be agreed with or they will deny the transfer of goods; someone concerned with themselves first.

"Kunde," in German, comes from the German word cundo meaning "associate, fellow, friend" coming from Old High German chund and from the Anglo Saxon cúþ meaning "becoming acquainted, noted, known."

My thoughts on the German word kunde: This is a person about whom we have knowledge. The sidebar conversations at the Symposium also suggested that in modern usage, a kunde also had a negative connotation of someone to whom we paid money (or some other unwelcomed effort) or who was troublesome to deal with, rather than someone who brought us money.

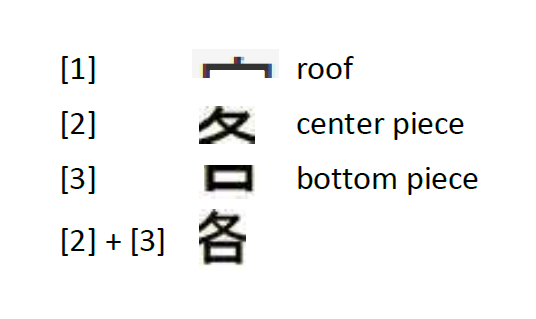

"Kyaku," in Japanese, is written with kanji character which is composed of several elements. The top piece [1] is a roof indicating a house that is not one's own; in other words, a stranger. The center piece [2] is a man, who is walking slowly, hindered by his elaborate clothing, and when combined with the bottom piece "mouth" [3], yields a meaning of: To go one's own way without hearing the advice of others, that is, an individual described by his self-love, his own way.

My thoughts on the Japanese word kyaku: This is a stranger in our home who is limited by only seeing the world through his own eyes, unable to understand what we might tell him.

What insight can QFD practitioners gain from these words?

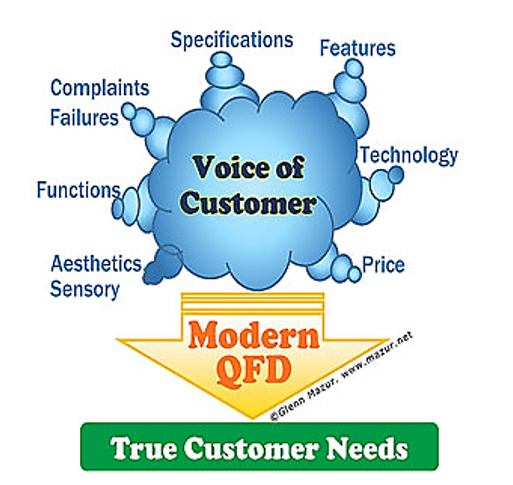

Customers see things from their perspective, not ours, regardless of how connected we may think we are. We must work hard to understand what is going on in their unspoken thoughts. Modern QFD tools such as the Customer Voice table was specifically created to translate the spoken into the unspoken true customer needs.

Customers have practices or usages of their own. To satisfy them, our products must fit with their practices, not be foreign to them or ask them to change their ways to use our product. Modern QFD tools such as the Customer Process model helps us to understand the customer's practice step-by-step so we can better understand how we can help him/her improve it.

The customer is the key to transferring ownership of our product from us to him/her in exchange for money. He/she is by nature difficult to deal with, insisting that things be done to his/her satisfaction or it's "no deal." Modern QFD tools such as the Maximum Value table help us identify solutions to the customer's most difficult needs so that he is satisfied with our product.

The customer is the one who brings money, rather than someone who costs money. Customers have to be cared for as travelers or guests under our roof. While they may not fully understand us, it is our obligation to try to understand them better than our competitors, if we want their business.

"The customer is a pain" is a common expression today among busy, harried producers and providers. I would like to re-spell this as "the customer is a-payin', " meaning that our customers are payin' our house, payin' our car, payin' our food...

Remember the story of Keystone Customers. The end-user, the consumer, is the the only person who puts money in the supply chain of any product or service. Everyone else (CEO, president, R&D, design, marketing, sales, production, suppliers, and so forth) is simply passing the customers' tokens up and down the chain. Without customers, our companies, jobs, and salaries would disappear.

These days, customers have more and more choice from producers and providers around the world. We must continuously earn and re-earn their business. While ongoing product improvement from six sigma projects help improve our products, only QFD can help improve the customer's process.

This requires gaining an intimate knowledge of the customer and what prevents or enables their success in their own life or business. This requires a collaborative effort by marketing and engineering to explore first the customer and then how to deliver an effective solution to their most important needs. And finally, this requires empathy with customers.

At one of the presentations in Stuttgart, the speaker expressed his disappointment that when talking to customers, they learned of interference between their product and another product commonly used by the customer.

Since the other product was not related to their technology, their company's engineers were completely uninterested in addressing the problem. Rather than seeing this interference as out-of-scope, the company should recognize that their competitors also create an interference for customers and that solving this could create significant advantage.

Solutions could include:

working with the makers of the interfering product to develop a solution;

the company creating or buying a producer of the interfering product in order to provide a solution package for the customer;

the company adding a non-interfering function to their product that would make the interfering product unnecessary (and thus reducing cost and complexity for the customer), etc.

These and other ideas could also prevent the producer of the interfering product from entering their technology domain by collaborating with their competitors.

Seeing this big picture requires a high-level perspective of the customer and just getting Voice of Customer (VoC) is not good enough. What is required is a systematic approach to understanding the customers in their gemba (in situ) and deploying this understanding into product design and delivery quality.

Unfortunately, traditional approach House of Quality matrix (HoQ) occurs too late to capture this necessary insight. The tools in modern Blitz QFD® including the above mentioned Customer Process model, Customer Context Table, Customer Voice table, and Maximum Value table were made specifically for this purpose.

Whether you are new to QFD or a seasoned veteran, the QFD Green Belt® and QFD Black Belt® courses will help you gain expertise in these tools, as well as improve your understanding of the correct use of the House of Quality and other matrices.

We want you to succeed. Your customers want you to succeed. So, join us. Bring a team of marketing, engineering, production, and quality and learn these modern tools by applying them to your own project in the class.