"Mom, I think I broke my leg," cried Mary's daughter in a telephone call that every parent dreads about receiving. Alone in Germany, thousands of miles away from her U.S. home, Mary's daughter had a collision with a car while riding a bicycle to college where she was an exchange student.

After frantically contacting the college coordinator, Mary's daughter was seen by a respected village doctor, who felt her leg and told her, "The bone is not broken; just rub your leg and it will go away."

The mother and daughter were relieved at the news of no fractures, and they chuckled about the eccentric way the German doctor responded.

A week later, Mary received another emergency call. Her daughter said that her leg had developed a huge purple blob and excruciating pain. Another examination was performed by the same doctor in the same manner. "Rub it with your hands and it will go away," the doctor repeated and refused to do additional testing.

By this time, Mary was anxious and frustrated. After consulting a friend who works in a hospital, she arranged for her daughter to fly home to America during the upcoming winter holidays, so that she could be seen by their family physician. After a series of X-rays and high tech testing, lo and behold, the American doctor reached the same conclusion: No bone was broken. It was a case of hematoma and the best treatment, in this case, was to continue massaging the area with hands.

This case illustrated, at first impression, a different attitude employed by the German and American physicians. While the German doctor refused to order X-rays, saying it was not necessary, in the U.S. both patients and doctors tend to seek high tech tools more often either because they are readily available at the point of care, the way the US insurance works, or doctors are more concerned about the litigious nature of US medical practice.

The cost impact of these differences can be easily pictured. But it would be shortsighted to say which approach is better simply based on this example, because an auto accident could cause serious fractures and tears that cannot be determined by touch or vision. Mary's daughter turned out to be a lucky case, considering her bicycle was totaled in the accident.

What was intriguing about this case, from a QFD perspective, was the issue of communication efficacy in health care, namely cognitive information processing. The diagnosis was correct and no medical error was made. Yet, it took an expensive international flight back home and a third examination for the patient and mother to come to understand the meaning of the original diagnosis.

Perhaps foreign language barriers compelled the German doctor to limit the information to a bare minimum and made Mary's daughter reluctant to ask questions. But when the patient insisted on being seen again for the same condition in a short time and it was found she did not follow instructions and the injury worsened, didn't it signal that the previous communication had failed? Had the doctor been able to pick up this clue and taken a different communication approach, would the patient have had to go through everything that happened afterwards?

In his New York Times bestseller “How Doctors Think,” Dr. Jerome Groopman, M.D. reports that some 80% of medical misdiagnoses that caused serious harm could be attributed to a cascade of cognitive errors, while only 4% was traced to inadequate medical knowledge, according to studies done by medical quality researchers. For example, in a study of 45 doctors in California caring for more than 909 patients, two thirds did not tell the patients how long they should take the new medicine or what side effects could be possible; half failed to specify the dosage.

"Modern medicine is supported by an array of high-tech tools, such as MRI, DNA analysis, etc. But language is still the bedrock of clinical practice," writes Dr. Groopman. "The questions you choose to ask and how you ask them will shape the patient's answer and guide your thinking."

"If you listen to the patient, he is telling you the diagnosis"

... William Osler, 1913, Brigham Hospital ...

There are many parallels between the cognitive processing in medicine that Dr. Groopman is trying to raise awareness of and what we QFD practitioners try to achieve with the modern Voice of Customer analysis.

In one example he cites, an elderly man arrived at an emergency room (ER) after injuring an ankle from tripping on the street. Like Mary's daughter, he wanted to be reassured it wasn't broken and be given something to relieve the pain. Everyone in the ER focused on his ankle, based on the patient's words. Only much later when the patient casually mentioned his clumsy footsteps and frequent falls, a doctor began to wonder there might be more than the stated, obvious injury. It turned out that this man was weak from anemia, which was subsequently traced to undiagnosed colon cancer.

In new product/service development QFD, we always stress the importance of going beyond the stated customer verbatims and uncovering both “spoken" and "unspoken" true customer needs. That is because customers do not always know or articulate what they want. What they say they want is often the best approximation of what they think is available or permitted, based on their past experience of a specific product or service. They do not know about the new technology that the producer is developing or what they could or want to do with it if it becomes available.

The healthcare environment is no different. Not only that, medical practice involves life and death decisions, so good listening skills and information processing is extra important. In clinical medicine, what exacerbates physician-patient communication quality includes, according to Dr. Groopman, the frenzied pace in which doctors and nurses are expected to function these days, but most importantly, the way cognitive information is processed in arriving at a diagnosis.

Today most medical students are trained on Bayesian analysis, a method of decision-making that uses preset algorithms and guidelines in the form of yes/no decision trees, adhering strictly to evidence. Insurance companies have found this approach attractive in deciding which diagnostic tests or treatments to approve. But the QFD professionals have known that such linear analytic approaches can be useful for solving routine problems but it is less effective when outside-the-box thinking is required — because "once you run out of decision tree branches, you have depleted solution options,” says Glenn Mazur of the QFD Institute.

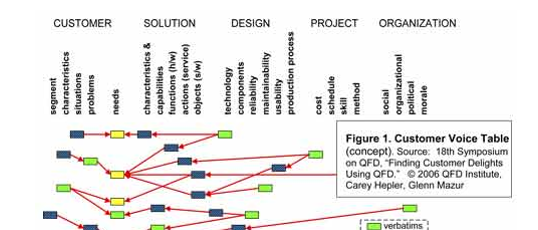

For example, when a patient replies in a survey, "I want a good sleep," the service excellence team of a hospital using a linear decision-tree approach might jump to the specific measures that induce patients sleep, such as dispensing a sleeping pill or sound abatement. Meanwhile, by using the Modern QFD's Customer Voice Table tool, the same Voice of Customer could be translated to multiple needs such as "I want to wake refreshed," "I want to wake up and be able to move around easily (no back ache)," "I want to wake up alert," etc.

The same tool enables hospital administrators to translate another VOC example, "I wish I could make a same day appointment to see my doctor, without having to go to the Emergency Room," into multiple customer needs such as:

"I want my health issue addressed immediately."

"I don't want to wait for unnecessary tests."

"I want to be seen by a doctor who is familiar with my pre-existing conditions and medical history."

"I want to know if there is anything I should avoid doing because it will make my condition worse."

"I don't want to catch anything from another patient."

"I don't want to pay extra for ER treatment," etc.

By deploying these customer needs through the Blitz QFD® process, the hospital could identify new niche markets, establish better business strategies, develop new patient services, and improve existing processes.

As we work on improvement of many healthcare issues and patient-oriented care increases in importance, Modern QFD tools can be easily adapted to all areas of healthcare and medical device industry, from patient care improvement to development of new healthcare services, new medical device, medical bio-technology applications, as well as strategic development of these industries.

We could also see improvements in insurance development and aligning cross-functional and cross-specialty communications toward the common goal of better patient care and efficiency.

Furthermore, these Voice of Customer and analytic tools and deployment techniques are equally adaptable to any industry and project, as demonstrated in many case studies.